Three schoolboys pedal off to Europe in 1966

Marking 50 years since my first cycle tour in Europe

On the afternoon of Saturday 30th July 1966, the England football team beat West Germany at Wembley in the final of the World Cup. Tom McLoughlin, a 17-year-old schoolboy from Reading, attended the match. Early next morning, Tom and two of his classmates – Martin Taylor and myself – set off on our bicycles for the continent of Europe.

It’s hard to imagine today how exotic the Continent seemed in the mid 1960s. Although by that time some ordinary British people were able to afford foreign holidays, there were still plenty, including myself, who had never left the UK. For many families, including much of the British middle class, Europe was just too expensive to visit. But Tom, Martin and I had a solution which overcame the fact that our parents could not afford foreign holidays; we got on our bikes and pedalled east, leaving our homes in the Reading suburbs of Tilehurst, Southcote and Calcot far behind. Not for nothing is the bicycle sometimes called ‘the freedom machine’.

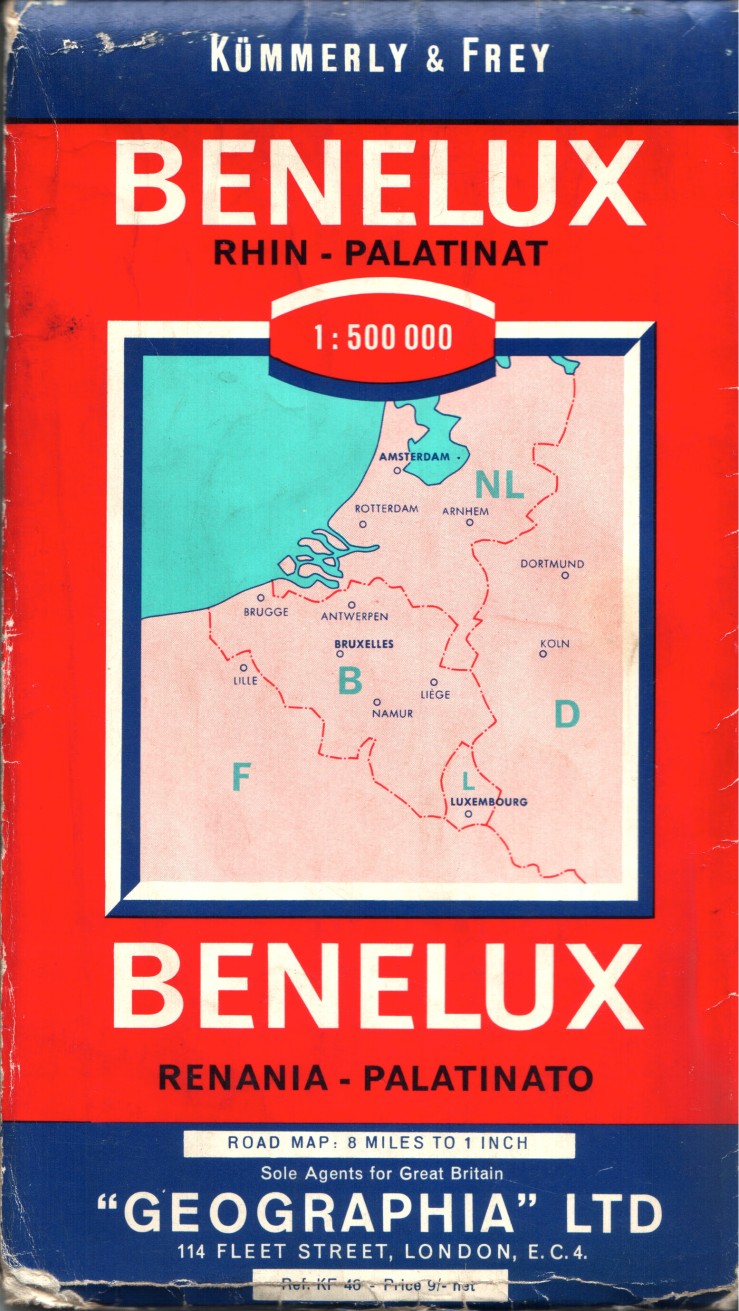

A lot of planning went into this trip, a process which I took on and greatly enjoyed. I made numerous visits to the travel section of our splendid new public library. I wrote to national tourist offices for free leaflets, brochures and maps. I bought a fine Swiss-made Kümmerly & Frey map of Belgium and the surrounding parts of Germany, the Netherlands, France and Luxembourg. I also bought some of the new Collins pocket travel guides, which were splendidly concise, compact and affordable. And I closely studied ferry timetables and youth hostel year books.

The original idea had been a cycling holiday in France. In the 1960s popular mind, a cycling holiday on the Continent was synonymous with a cycling holiday in France. It was something Brits had heard of but which few actually experienced or wanted to. It was something a friend of a colleague’s cousin might have done a few years ago. It was generally viewed in much the same way as bungee jumping is today – an activity for intrepid people who are a bit odd.

We didn’t care about the social attitudes but we did want an enjoyable and interesting holiday, not an endurance test of how many miles we could cover on our bikes. We noticed that France is very big and major towns are generally a long way from each other. So should we opt for the default French cycling tour or something else? And if we chose something else, wouldn’t that be even more expensive than France and therefore out of our price range?

Whilst studying a school atlas, I noticed a neat and compact little country called Belgium. Like most Brits, we didn’t know much about Belgium but the more I read up about it, the more I liked it. It had a fascinating history, closely linked to our own. In the north-west it had splendid world-class medieval art cities, conveniently only a few hours of cycling apart from each other and in flat countryside. In the south-east it had rolling countryside with river valleys and forests. And it bordered West Germany, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and France. Better yet, the ferry to Belgium was no more expensive than the short French crossings. So we decided that Belgium would be where we would do most of cycling, but with a few days in West Germany and maybe the Netherlands, too. Our aim was a fortnight on the road, which was about as much as we could afford.

Day 1 – Sunday 31st July 1966

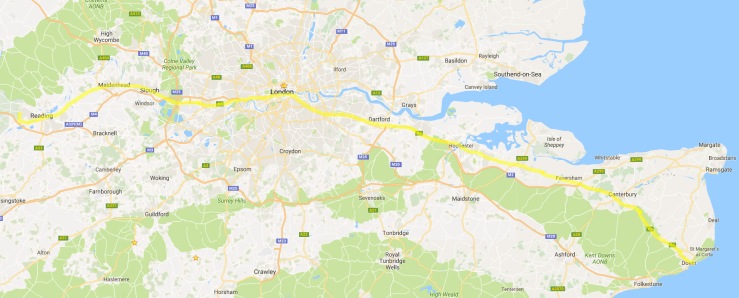

When we set off early on Sunday 31st July 1966, our target was Dover, where we were to catch an overnight ferry to Ostend in Belgium. Reading to Dover was about 125 miles, which was more than any of us had cycled in a day. In fact, it was about twice as far as we had ever done in a day.

Today, finding an easily navigable, straightforward and reasonably safe route to cycle from Reading to Dover would be quite tricky. (Yes, there are the Sustrans routes and smartphone apps but they can be frustrating to navigate.) But 50 years ago, when traffic levels were about a tenth of what they are today, we just went straight up the A4 Bath Road from Reading to London, straight through the middle of the city, and out down the A2 to Dover. It took a while to get used to the effect of being passed by trucks, which first buffeted you, then briefly dragged you along in the low air pressure area behind them. But apart from that, it wasn’t too bad. In fact, it’s amazing to recall how little traffic there was on these major routes on a Sunday in ’66.

The morning went very easily. As we all came from church-going families, in which such matters were taken very seriously, we stopped off in Maidenhead to attend a mid-morning service. Haloes polished, we carried on to London. Tom, having witnessed the England victory at Wembley only some 19 hours earlier, was delighted when we spotted England captain Bobby Moore driving his car. What an amazing coincidence!

On we pedalled through the London suburbs and into Kent. The weather was good all day: not too hot but pleasantly warm, neither windy nor wet. Eventually, after cycling in built-up areas almost all the way from Maidenhead in Berkshire to Bexleyheath in Kent, we started getting into a more rural landscape. There were actually green gaps between some towns!

This was the era of offshore pirate radio, which in 1966 was at its peak in the UK. I shall always remember looking north, from the A2 near Whitstable, at Redsand Fort, a WW2 anti-aircraft installation about 7 miles away in the shimmering water of the Thames Estuary. Redsand Fort was the home of Radio 390, a very professional station with a powerful signal, aimed more at our parents’ generation. But, in the early evening, we often listened to 390, because it had the best RnB, blues and soul show on British radio, hosted by the late great Mike Raven.

Somewhere along the A2, Tom fell off his bike. But no significant damage was done to rider or machine.

On we rode and, by early evening, the strain was beginning to tell a little. Martin, who was younger and smaller than Tom and myself, struggled a bit to keep up. But by about 9.00pm, as light was starting to fail, we finally arrived at Dover ferry terminal. In fact, we had done very well. We had covered about 125 miles in approximately 14 hours, including about an hour in a church service and a few short breaks for food and drink. So our average speed while in the saddle must have been about 10mph. There were no punctures or mechanical failures, no navigational errors and the weather had been kind. As we embarked on the passenger ferry, we were tired but elated and very excited about the next stage of our journey.

Digression No.1 – the Bikes

The bikes we three lads rode differed considerably. They were all, in one way or another, a cut above the so-called ‘sports bike’ that was the standard schoolboy machine of the day.

Far from being a racer, the ‘sports bike’, sometimes described equally erroneously as a ‘light tourer’, was what the cycle trade would later call a ‘sports light roadster’ or SLR for short. (The ever-evolving language of marketeers is a wonderful thing!) This default aspirational schoolboy machine, the promise of which was often used by richer pushy parents as an inducement to pass the 11-plus (a selective secondary education exam), typically had 26 x 1⅜-inch wheels with full mudguards, a 3-speed hub gear, so-called all-rounder handlebars (fairly flat and but not as straight as mountain bike bars), pedals incorporating rubber blocks for grip, a ‘hockey stick’ chain guard and a sprung mattress saddle. All the ‘brightwork’ metal components were made of chromium-plated steel and the frame would be finished in a bright colour, sometimes with a two-tone finish, with white flashes offsetting the main colour. It was a modern-looking compromise between your granddad’s heavy, big, black, sit-up-and-beg roadster and a proper tourer or racing bike. But it owed much more of its DNA to the roadster than to a racer.

So what did we three boys ride? Certainly not one of the above ‘sports bikes’. Martin rode a dark green Halfords own brand ‘racer’, which he borrowed from his older brother. It had 27 x 1¼-inch wheels, drop handlebars, a leather racing saddle, metal ‘rat-trap’ pedals and 10-speed derailleur gears. Nobody would have seriously raced on it, as all the components were down-market heavy steel but it looked quite flash. It was also a bit big for Martin but he coped with it very well.

At first glance, Tom’s machine looked similar to Martin’s, apart from the colour, which was silvery grey. It had the same size wheels, similar handlebars, pedals, saddle and gears but all lighter and better quality. Tom’s bike was ‘the real deal’; a proper clubman’s bike, with quality alloy components. Very few schoolboys owned such a machine, which would have represented about a month’s pay for many fathers. In fact, I can’t remember any other classmates or friends owning such a high quality bike. I think Tom’s was a Falcon, made in the days when that brand was a genuine builder of quality lightweights.

As for me, ever the non-conformist, I rode a colorado red Moulton Speed with chromium-plated mudguards, which I had bought on hire purchase in November 1964. This was a completely radical machine, with 16 x 1⅜-inch wheels, full suspension and a 4-speed hub gear. It had big low carriers fore and aft that could safely carry 70 pounds of luggage. It was not the Speedsix racing version or the Safari full-on tourer. It was, nonetheless, quite sporty, with a leather racing saddle, steel rat-trap pedals and down-turned all-rounder handlebars on a long forward extension which, to my adolescent mind seemed rather sexy. (An indication, perhaps, of how sad teenagers can be!)

For those who don’t know, the Moulton bicycle became a British icon of the 1960s. It first caught my attention late in 1962, when John Woodburn (whom years later I had the honour of getting to know) broke the Cardiff-London record on one. In the mid-1960s, Moulton production peaked at a thousand bikes a week. The new machine turned the British bicycle industry on its head, arresting a steep post-war decline in UK cycle production by reigniting interest in cycling, hitherto increasingly deemed an occupation of the poor and under-privileged. More than a decade after the Moulton was launched, the mighty Raleigh’s biggest seller was a small-wheeler produced in response to demand created by the Moulton.

The great thing about the Moulton from my point of view was its multifunction capability. It was my daily personal transport, getting me to and from school and everywhere else I needed to go – about 50 miles a week. It was pretty fast and I never lost any informal race on the way to or from school. It accelerated markedly faster than a conventional bike, which meant when the light turned green, I got away first. Importantly, its superb luggage carrying capability enabled me to carry two newspaper rounds on it, which is how I earned most of my money.

(Cue soulful violin …) My Dad gave me only a shilling (5 pence) a week pocket money and my paternal grandmother gave me two shillings (10 pence), but, with the paper rounds done on the Moulton, I literally cranked my income up to more than a pound a week. That was how I was able to pay for the Moulton and the Continental cycle tour. So the bike was at the hub of a virtuous circle: it helped me earn the money to escape the pleasant dullness of English suburbia and then provided the means of transport for that very escape. Not quite Steve McQueen jumping the barbed wire on his motorcycle but as near as I was going to get in 1966.

As this tale of the tour progresses, I’ll tell you more about how each of these bikes performed.

Day 2 – Monday 1st August 1966

I have no recollection whatsoever of eating anything between leaving home the previous morning and arriving in Belgium. I’m sure we would have taken home-made sandwiches with us and we probably bought chips in Dover. I’m not sure we could afford fish to go with the chips.

The ferry from Dover to Ostend, operated by the state-owned Belgian Marine, departed about half an hour after midnight. It was small by modern standards, one of the last cross-channel packet boats. That designation meant it was a passenger and light cargo vessel rather than a ‘roll-on-roll-off’ car ferry. Consequently, our bikes were heaped up on a pallet and we looked on with some trepidation as they were craned into the hold.

I wasn’t a great sailor and, for anyone having trouble with the rolling and pitching of the boat, the smoky interior was enough to make you want to throw up. So we went on deck, where the air was fresh, and joined a whole gang of European teenagers. This was great, as we had met very few ‘foreign’ youngsters previously. There were boys and girls from Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg. Everybody was having a great time, chatting and listening to British pirate radio (Caroline or ‘Big L’) on ‘trannies’. (I should explain that, in those days, a ’tranny’ was a small portable wireless and not what it means today.)

We were very impressed at how well most of these friendly kids spoke English. I asked one Dutch guy how it was that he spoke English so fluently. He told me it was easy for him, because his parents only had a small TV. The Dutch broadcasters didn’t dub English-language films into Dutch; they merely added subtitles. But because the TV was small, he couldn’t read the sub-titles; he just absorbed English through watching TV.

After all our cycling, we really should have tried to get some sleep. But we were so excited that we just chatted all night. The crossing to Belgium took about four hours. The boat initially headed straight for the French coast and then sailed parallel with it, a few miles out to sea, until we came to Ostend. Or, as the locals would spell it in their native Flemish, Oostende – meaning East End.

It was not yet dawn as the packet boat approached Ostend harbour. It was a pretty place, with all the navigation beacons, the floodlit cathedral and the three-masted sailing ship Mercator also lit up. Mercator was named after the famous Flemish cartographer (he of Mercator’s projection and one of a surprisingly large number of famous Belgians). She was a training ship and scientific research vessel, designed in Belgium, built in Scotland and launched in 1932. Fifty years later, she’s still in Ostend harbour but is now a museum ship.

We didn’t have to adjust our watches for Belgian time, as in those days Belgium and other western European countries didn’t switch to Energy Saving Time from spring until autumn. The UK was on British Summer Time (an hour ahead of Greenwich Mean Time) which coincided with Central European Time, as used in Belgium, the Netherlands, West Germany and many other countries.

Many of the ferry passengers went straight to the nearby railway station, from which you could travel direct to Vienna. Until the 1960s, you could even take a direct sleeper train from Ostend to Istanbul, as in the Graham Green novel ‘Stamboul Train’.

We, meanwhile, waited while our bikes were craned out of the hold. Fortunately, they had survived the crossing without damage and we were soon on the road. Straightaway, I was aware of those little differences that give countries their individual character. For example, the massive electricity pylons around the port were quite different in design to the British ones. Also, most of the roads were surfaced with the infamous Belgian pavé – rectangular stone blocks. But – wonder of wonders – there were proper cycle-paths almost everywhere. This was quite a boon, as we instantly had to come to terms with the fact that Belgium (in common with the rest of western Europe) drives on the right-hand side of the road. Whereas in the UK and Ireland, right is wrong when it comes to driving.

Ostend was linked to Brussels by one of Europe’s first motorways but, needless to say, bicycles weren’t allowed on it. So we followed the old main road to Brussels, using those very welcome cycle-paths. The dual suspension on my Moulton bicycle helped ensure a pretty smooth ride on the pavé. As we cycled away from Ostend, down the Torhout Steenweg (‘steenweg’ literally meaning ‘stone way’), the sun came up. It marked the start of what was to be a very long day. We soon noticed that every village had its name sign sponsored by the Belgian tyre maker Englebert, which was quite a neat idea.

The landscape of West Flanders was famously flat. Some people find flat landscape boring. But as I lived on a steep hill, in a hilly part of southern England, flatlands were a novelty for me and I found them interestingly different.

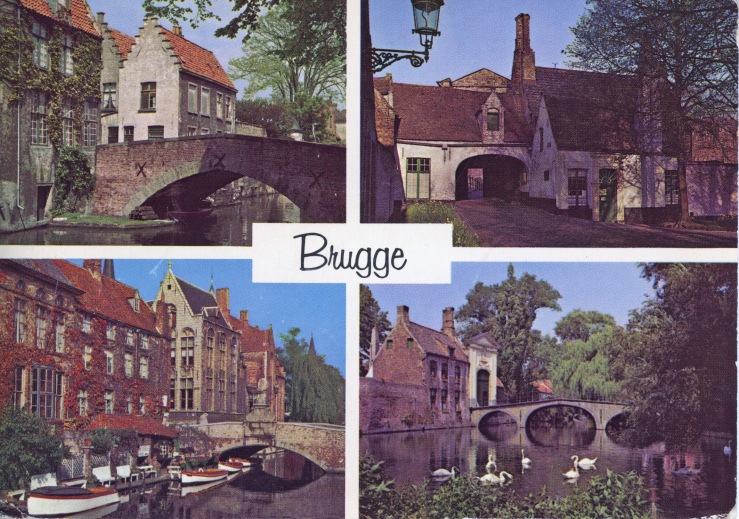

The first major town we came to was Bruges (Brugge in Flemish, meaning ‘bridges’). Back in the Middle Ages, this beautiful city was one of the four biggest in Europe. It was a major international trading centre, with close links to England and many other places. But gradually the inlet to the sea silted up and the town became commercially fossilised. (Much later a new port was built – Zeebrugge, meaning ‘Sea Bruges’.)

The medieval buildings were well built by the city’s once prosperous burghers and stood the test of time. So today Bruges is one of the best preserved medieval cities in Europe. However, we didn’t have time to explore the place; we intended doing that on the way home. Today’s objective was to reach Brussels, which was still about 70 miles away. Also, our pace was continually dropping compared with the previous day. Our main priority in Bruges was to get something for breakfast as quickly and cheaply as possible, then get back on the road.

It was almost 7.00 in the morning when we arrived on the outskirts of the city. Some shopkeepers were already setting up for the day and by the time we reached the city centre, the wonderful bakeries and cake shops were open for business. What amazing cakes – so superior to what we were used to in England. Guess what we had for ‘brekkers’!

Soon, we were on our way out of Bruges, following the signs for Brussels. A few miles south of the city, we cycled up a ramp onto a smooth dual carriageway – a nice change from the pavé we had been riding on before. Almost immediately, we were pulled over by the ‘Politie’. Why? Because we’d inadvertently got ourselves onto the Ostend-Brussels motorway! The Flemish policeman was polite but firm and we had to push our bikes back to the slip road, cycle back into Bruges, then find the old road for Ghent and Brussels. We must have lost half an hour or more due to that mistake.

Once we were on the right road, we cruised steadily eastwards, heading next for Ghent (Gent in Flemish, Gand in French), about 30 miles away. As we moved from the province of West Flanders into East Flanders, the landscape remained flat. (A Belgian province is equivalent to an English county.) The sun shone brightly, there was not a hint of rain and I’m sure we were aided by the prevailing south-westerly winds. I was wearing a short-sleeved shirt and my arms turned brown that morning and stayed that way for years, the tan topped up by further cycling.

In the countryside and villages, apart from charming old farmhouses that could have come from an old Flemish landscape painting, we noticed many fine post-war houses. The standard of housebuilding seemed high and most new houses looked as if they were architect-designed. The brickwork differed from the British style, many of the bricks being less tall and sometimes longer. Apart from the normal pinks and reds, they were often in a shade of buff or yellow. It was the Flemings who re-introduced bricks to England in the Middle Ages. The Romans used brick in Britain but the Anglo-Saxons didn’t. Any decent English bricklayer will build you a wall in Flemish bond.

Another feature of Flemish houses was the big TV aerial rigs. It may seem odd today but, back in the 1960s, European countries typically had between one and three TV channels each. But people in Belgium, a small state surrounded by other countries, could usually pick up at least some of the neighbouring states’ programmes. So a typical Flemish house had a mast about 10 feet high mounted on the ridge of the roof and guyed back to the four corners of the roof. Atop this mast (usually a vertical lattice beam) was a stepper motor with a big array of antennas, capable of receiving all TV bands. Inside the house, next to the TV, would be a box with the points of the compass on it and a knob. If you wanted to watch Dutch TV, you turned the knob to ‘North’ and the antenna rotated to face the Netherlands. If you wanted French TV, you turned the knob to ‘South’. And, if you lived near the coast, you could try ‘West’ and you might get British TV. Naturally, you could also get Belgian TV. These big aerial rigs were almost standard in Flanders in the pre-cable era and would probably have cost more than the TV. But there were not many other places in Europe where viewers had a choice of up to a dozen channels – provided they could understand French, Dutch and English. Many Flemings could.

Another common feature of Belgian houses was an aspidistra in the front window. In Britain, aspidistras were completely out of fashion by the 1960s, a symbol of a bygone, dusty and old-fashioned age. They were mentioned in comic songs sung by Noël Coward and Gracie Fields. But in Flanders aspidistras were prospering in the 1960s.

About halfway between Bruges and Ghent, we were getting very thirsty. In those days, it was quite normal for a stranger to knock on someone’s door and ask for a glass a water. So that’s what we did. A very friendly Flemish lady, about 40 years old, came to the door. We made our request in English, as we had no Flemish/Dutch and I knew that Flemings could be offended if you addressed them in French. (I’ll explain why in a later digression.) The kind lady quenched our thirst and wished us a good journey. It occurred to me that she would have been our age – a teenager – when British soldiers of our parents’ generation liberated her country from the Nazi occupation. When you are young, 22 years seems a very long time. But as you get older, it’s like only yesterday. I think that memories of 1944 accounted to quite a large extent for the kindness and friendliness we received from older Belgian people in 1966.

It must have been about midday or later when we reached Ghent, another beautiful and well-preserved medieval Flemish city, with long cultural and trading links to England. (For example, John of Gaunt means John of Ghent and he got married in our hometown of Reading!) We stopped at a cafe for refreshments and were aware that, although we were under age to buy alcohol in England, in Belgium we were not. I’m not sure whether we actually drank anything alcoholic on that occasion. Maybe a cheeky little pilsner lager? But I suspect we stuck mostly to soft drinks, as we still had 30 miles or more to ride and it was a hot day.

Through the afternoon we cycled on towards Brussels. Fatigue was really showing now and our speed was dropping more and more. We passed from East Flanders into the province of Brabant. The landscape became more rolling and the farming emphasis shifted from smallish fields with cows, horse and pigs to market gardening.

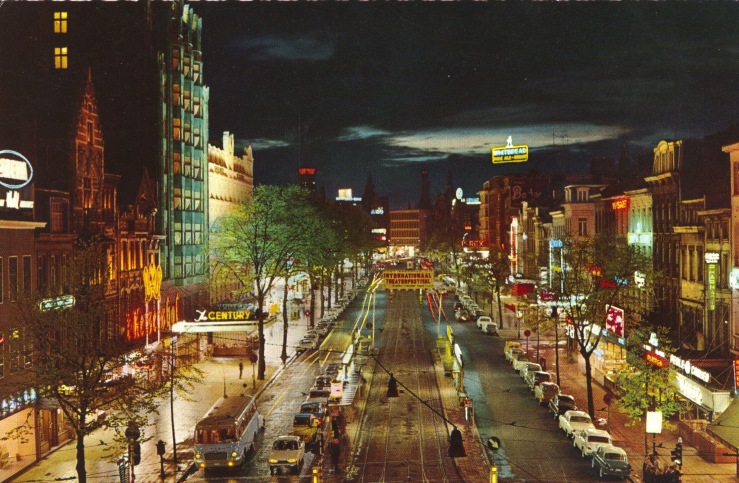

In the early evening, we finally reached the western outskirts of Brussels. It was quite a thrill to experience this large city with its wide boulevards. I particularly remember a big poster that we saw several times on the gable ends of buildings. It showed a huge steam engine puffing out black clouds of smoke. The poster proudly proclaimed that ‘this source of pollution has now been eliminated’. Belgium, the first country in mainland Europe to have a steam railway, had just scrapped mainline steam engines, two years before the UK. Steam clearly held no romanticism in the eyes of the Belgian government.

That poster appeared in both Flemish and French versions, highlighting the fact that the Belgian capital – historically Flemish and surrounded by Flemish speaking Brabant – was officially bi-lingual. There was a big struggle going on between the more extreme supporters of the two languages. Road signs in Brussels showed place names in both languages. So the road to Liège (French) was signed also as Luik (Flemish). But often, one or other of the campaigning groups would paint out the other version. In the worst tit-for-tat cases, both versions of the place name were sprayed out! Brussels itself, needless to say, has two names: Brussel in Flemish and Bruxelles in French.

I was the navigator for this tour, so I now had recourse to a street map of Brussels, procured in advance, to find our ultimate destination, in the south-east of the city. We were getting quite close to journey’s end when, as we passed the Berlaymont building, headquarters of the Common Market, Martin’s chain came off. It was not the sort of problem we needed after all that travelling, but it was quickly and easily rectified. Also during our time in Brussels (I’m not sure precisely where and when), Tom dented one of his alloy wheel rims on a tram track, but the damage was not bad enough to hold us back.

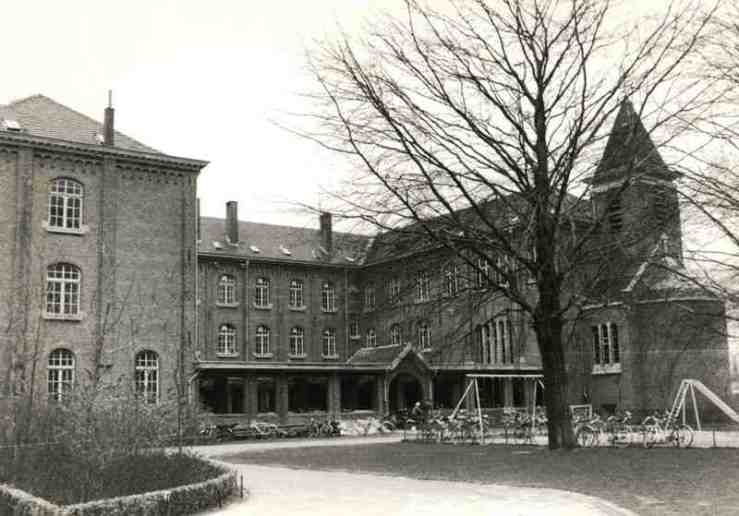

For overnight accommodation on the tour, we were generally relying on youth hostels. However, our parish priest (a friend of my parents) had suggested making use of ‘monastic hospitality’. I was amazed when he first suggested this. I knew that, in the Middle Ages, travellers could knock on the door of an abbey and ask for basic accommodation at little or no cost. But I had no idea you could still do it. The priest assured me you could, so I wrote to the Belgian Tourist Office in London and asked for a list of monasteries that might provide such a service. I don’t think they were convinced that it would work but they nonetheless provided a list of about half a dozen places. One was a seminary (a training college for priests) at 205 Chaussée du Wavre in Brussels. (That’s 205 Wavre Straat in Flemish. All places in Brussels have French and Flemish names but from hereon I’ll stick to the French for simplicité.)

So, almost exactly 36 hours and 211 miles of cycling after leaving Reading, and with no sleep on the way, we arrived on the doorstep of a Catholic seminary. A rather puzzled concierge came to the door. He had no English, so we explained in schoolboy French what we wanted. He went off, still looking puzzled, and fetched a priest, a very nice chap called Father Wolf. Yes, of course, he said, come on in!

The students were all on vacation, which meant that the dormitories were empty. We were given free range to sleep there. Better yet, we were invited to join the priests for supper after we had freshened up.

At supper, there were about a dozen clergy sat at a big refectory table. They were all very well-educated people; professors of theology and that sort of thing. Some had travelled extensively. I was particularly impressed that Father Wolf, whom I think had worked in the USA, knew how to pronounce Reading properly! Most non-native English-speakers pronounce it like ‘reading’.

These venerable Belgian clergymen treated us three scruffy and exhausted English teenagers very well. There was no condescension at all and they shared their valuable local knowledge on how best to get about the city.

Having eaten a fine supper, we three exhausted lads headed for bed. We were exhausted but also elated at how well we had done. And tomorrow we were going to explore Brussels.

Digression No.2 – language

Although there has been a region called Belgium for a very long time, the present-day Kingdom of Belgium dates back only to 1838-9, when Belgium broke away from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. (It’s rather like how the Republic of Ireland broke away from the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1922.)

Belgium has two main parts: Dutch-speaking Flanders in the north and French-speaking Wallonia in the south. There is also a small German-speaking area in the east, appropriated from Germany after World War 1. Dutch, French and German are all official languages of Belgium.

The capital, Brussels, was historically a Flemish city. However, over the centuries, French became the language of the ruling classes. Today, Brussels, though surrounded by Flemish-speaking Flanders, is officially bi-lingual. In practice, more of its inhabitants speak French as their first language than Flemish.

One of the factors that united the Flemings and the Walloons against the Netherlands was Catholicism. Belgium had a reputation until quite recently for being one of the most devoutly Catholic countries in Europe, on a par with how the Irish Republic was until the last few decades. Today, however, Belgium is one of the most secular nations in Europe.

Flemish is a form of Dutch and all Flemings can understand mainstream Dutch, which is taught in the Flemish schools and used in most formal publishing and broadcasting in Flanders. The difference between formal Dutch as spoken in the Netherlands and that spoken in Belgium is rather like the difference between standard British English and American English. There are differences of accent, idiom and vocabulary but the two forms of Dutch are mutually intelligible. However, what is spoken at home in a local dialect is something else altogether!

There is a cross-border organisation that ‘manages’ the evolution of Dutch; rather as the Académie française does for French but in a more sensible and pragmatic way. For example, soon after Word War 2, the Dutch and Belgians agreed to reform and simplify the spelling of Dutch. So, for example, the Flemish place name Passchendaele, familiar to students of World War 1 military history, is now spelled Passendal, representing better how it is now pronounced and saving quite a bit of ink.

In the newly formed Belgium of the 19th century, Flanders was an economically backward rural area. French-speaking Wallonia had coal and iron and became dominant during the industrial revolution. This economic supremacy, coupled with the ruling class’s use of French, made Flemish speakers second class citizens. Flemish was rejected not only by the government but by the army, the universities and the church. It took a long struggle, lasting into the 20th century, by Flemish artists, intellectuals and politicians to achieve equal status for their language. That was why Flemings might take offence if a foreigner sailed up to them and started talking to them in French. It was the assumption by foreigners that Flemings should understand French, coupled with the implication that French was Belgium’s first language, that was galling. In practice, most Flemings would have at least some knowledge of French and many were (and are) fully bi-lingual.

When we were in Belgium in the 1960s, the balance between the Flemings and the Walloons seemed fairly equal. However, over the next few decades, Wallonia rapidly lost its economic supremacy, as the old heavy industries became increasingly unprofitable. Meanwhile, Flanders modernised effectively, providing a welcoming home for new industries. Soon Flanders, which also outbred Wallonia, was the economically dominant part of Belgium.

Back in 1966, I realised that a lot of Flemish/Dutch words were very similar to their English equivalents, at least when written down. (It helped that we’d been studying Chaucer at school, because Middle English is even closer to Dutch.) For example, bread and butter in Dutch is brood en boter. The Dutch and Flemish live in a huis and enter through a deur. A Dutch or Flemish family might comprise a moeder, vader, zoon en dochter. We have summer and winter, whereas they have zomer en winter. We have water and mist and so do they. We might have a cat and a hound; they could have a kat and a hond. The kat could drink melk that comes from a kou.

However, the Dutch/Flemish pronunciation can sometimes mask these written similarities. Moreover, the pronunciation varies noticeably about every 6 miles as you travel east; so much so, that conversational West Flemish is often subtitled on TV so that Flemings further east can understand it. That’s comparable with Holby City (a soap opera set in the Bristol area) being subtitled so that people in Oxford could understand it!

It has been said that, if the Normans had not invaded England and injected so much French into Anglo-Saxon, English and Dutch would today be mutually comprehensible, in the same way that Danish, Norwegian and Swedish are.

Day 3 – Tuesday 2nd August 1966

On Tuesday morning, we awoke in the seminary dormitory, having slept very well indeed. We’d been invited (but not compelled) to attend a morning service in the chapel just down the corridor and it would have been churlish to have refused. I can’t remember much about it but I think it was a short and simple Mass.

One thing I can recall is that the chapel had ‘prayer-seats’. Unlike English churches, which tend to have traditional pews or chairs that clip together, these had a small, low seat and a tall back. You could sit on them in the normal way but when it came to a part of the service where the congregation kneeled, you picked up the chair (quite light) and spun it round through 180 degrees. You then knelt on the low seat and leaned forward on the backrest. These chairs were quite common in Belgium and France. I’ve heard them described as prie-dieu (pray-God) but a true prie-dieu is a prayer desk with a low kneeler and cannot be rotated to double as a seat.

Having been spiritually uplifted, it was breakfast time. Two things stick in my mind. Firstly, the coffee was excellent (proper ground coffee, not the indifferent instant variety common then in England) and it was drunk out of a bowl. Secondly, the milk bottle on the table bore the phrases ‘rincez moi’ (French) and ‘spoel mij uit’ (Flemish), meaning ‘rinse me out’. It’s funny how such odd little details stick in the mind.

One thing we travellers lived in fear of was ‘tummy bugs’. In those days, many Brits were very suspicious even of foreign tap water. (It was an article of faith, not entirely founded on fact, that only the British could do plumbing and drainage properly.) However, this was the 1960s and science had an answer for everything – or so we were told. Science’s answer to stomach upsets was not a traditional ‘after the event’ medication, such as kaolin and morphine (aka ‘concrete mixture’). Instead, the modern savvy traveller used a preventive medicine, taken daily while away on holiday. It was called Entero Vioform and everyone thought it was wonderful. I therefore religiously took my daily dose, despite the stuff being quite pricey.

However, some years later the active ingredient was linked to a massive outbreak in Japan of a serious disease of the nervous system. In most western countries, Entero Vioform was taken off the market. Today, we would tend to use Immodium, an ‘after the event’ medication developed, by happy coincidence, in Belgium.

So, having prayed, breakfasted, over-dosed on caffeine and protected ourselves from ‘the trots’, we three lads set off to explore Brussels. Although the Common Market then comprised only six countries (Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg, France, West Germany and Italy), Brussels was already being described as ‘the capital of Europe’ and we were keen to have a look at it. Thanks to the directions given to us by the priests, we easily got to the city centre. We left the bikes behind, preferring to use a mix of public transport and walking.

By then, we were coming to terms with Belgian money. There were 140 Belgian Francs to the British pound, which in those days comprised 20 shillings, each divided into 12 pence, each divided into 2 halfpennies. So a Belgian Franc was worth about 1.7 old pennies or 0.7 of today’s pence. ATMs, credit and debit cards as we now know them did not exist in Europe at this time (Barclaycard was launched in the UK that same year but only for the seriously rich), so we took a mixture of Travellers Cheques and cash.

We walked down the Mont des Arts and past the Royal Palace opposite the Parc de Bruxelles. Then we visited the famous Grand-Place. As Google succinctly puts it, the Grand-Place is a ‘huge city square completely encircled by elegant historic buildings dating back to the 14th century.’ It is, in fact, one of the most impressive medieval squares in the world, a real feast for the eyes. You can look up at any of the buildings and see innumerable subtle and elegant decorative features, such as carvings and weather vanes, many of them brightly gilded. It’s worth visiting just to stand there and look around. And it’s even better if you’ve first read up about the square’s amazing history. So many nations have occupied or controlled Belgium – Dutch, Spanish, Burgundians, French, Austrians, British and Germans – and anyone controlling the country needed to control this square.

Just off the Grand-Place is the famous Manneken Pis, a tiny 400-year-old bronze statue of a little lad peeing. (Manneken is Dutch for ‘little man’ and ‘pis’ needs no translation.) He’s the mascot of Brussels and has a whole exotic wardrobe of different uniforms and outfits which he wears for special events.

We spent quite a time wandering around the city centre, looking at the different kinds of shops and eateries – all very exotic if you lived in post-war suburban Reading. I made one significant purchase – my first ever 45rpm vinyl record. It was an ex-jukebox copy of ‘Wooly Bully’ by Sam the Sham and the Pharoahs, recorded in Memphis the previous year. Maybe buying my first record in Brussels was a portent, because from 1972 to 1974 I appeared every week on Belgian national radio introducing a new British single that I predicted would be a hit. But, of course, as a 17-year-old I had no idea that would happen!

Having had a brief introduction to the heart of Brussels, we set off by tram to the north of the city, to visit the Atomium. This is Brussels’ answer to the Eiffel Tower and was completed in 1958 for the World Fair, Expo 1958, as the main pavilion. The Atomium was therefore only 8 years old when we visited it. It’s an impressive and unique structure, about 340 feet high, comprising nine interconnected spheres, and representing an iron crystal enlarged 165 billion times. I’ve always found it ironic that the Atomium, modelled on an iron atom, is clad in aluminium. Anyway, it was well worth a visit, as the views from the top are amazing. On a clear day you can see all over the city and as far away as Antwerp.

Today, when youngsters go travelling, they can easily keep in touch with home via mobile phones, email and any number of apps on the internet. But back in 1966, there were no mobile phones and many families did not even have a phone at home. Moreover, the cost and difficulty of making international calls meant that they were only used in extreme emergencies. Nonetheless, despite the amazing trust placed by my parents in their 17-year-old son, I felt obliged to set their minds at rest as best I could regarding our progress. So I used the technology of the day – the postcard – sending four during the course of a fortnight.

Postcards also provided a practical and affordable way of getting images of the places we visited. Today, it’s easy and almost cost-free to bring back hundreds or even thousands of digital images from a holiday. But back then, film was expensive and I could only afford one Agfa-Gevaert 12-shot slide film for the whole holiday. I borrowed my brother’s Ilford Sport 4 camera, which was designed for use by kids and had just one adjustment – ‘sunny’ or ’cloudy’. It took large square colour transparencies on 127 format film.

From hereon, I’ll be including the postcards I bought and the photos I took on this tour.

Day 4 – Wednesday 3rd August 1966

On Wednesday morning, after another fine breakfast, we bid farewell to our hosts at the seminary. We offered to pay for our stay but Father Wolf very kindly said that this was not necessary. What a welcoming and encouraging start to our tour! I mentioned in my next postcard home that we had been given two days of ‘hotel-standard accommodation’ free of charge. Our parish priest had been right: monastic hospitality for passing travellers did still exist!

Tom, Martin and I now headed south, our aim being to spend the night at a youth hostel in Namur. The plan from hereon was to cycle about 30 to 45 miles a day, usually staying just one night in each place. Thus we could set out each day after breakfast, cycle to our destination by lunchtime, and then spend the rest of the day and evening exploring.

The weather, good ever since we left home, continued to be fine as we headed south through suburban Brussels. We briefly passed through a rural Flemish-speaking area just south of the bi-lingual city. Then we crossed the great linguistic divide: not just between Belgium’s Flemings and Walloons but between the whole Germanic language group (Dutch, German, English, etc) and the Latin-derived Romance languages (French, Italian, Spanish, etc). The strange thing about this border (which in those days was relatively unmarked) is that it simply runs through rolling open countryside. There is no range of mountains or mighty river separating the two tongues. It just seems that the lasting linguistic influence of the Roman Empire, as it expanded northwards, petered out in these Belgian fields, in a more or less straight line running (originally) from somewhere south of Calais to Aachen in Germany.

The most surprising thing to me is how static over hundred of years that linguistic boundary has been. Only in France, where Parisian French has been (and continues to be) firmly imposed on people who would otherwise speak local languages (such as Provençal, Picard, Flemish or Breton), has the boundary shifted significantly, and that has happened only in the last century or so. The area in question is around Dunkerque and Calais, from which Flemish has been all but eliminated. You have only to look at the placenames on a map to see where Flemish was once spoken: for example, Dunkerque is just a Frenchified version of Duinkerke, which is Flemish for Dune Church.

The linguistic divide also formed the border between the Flemish-speaking province of Brabant and the French speaking province of Namur. Today, Belgium is federalised, and that border is much more distinct. Flanders and Wallonia are significantly more independent of each other than when we visited in 1966, which was only three years after the language boundary was given legal status.

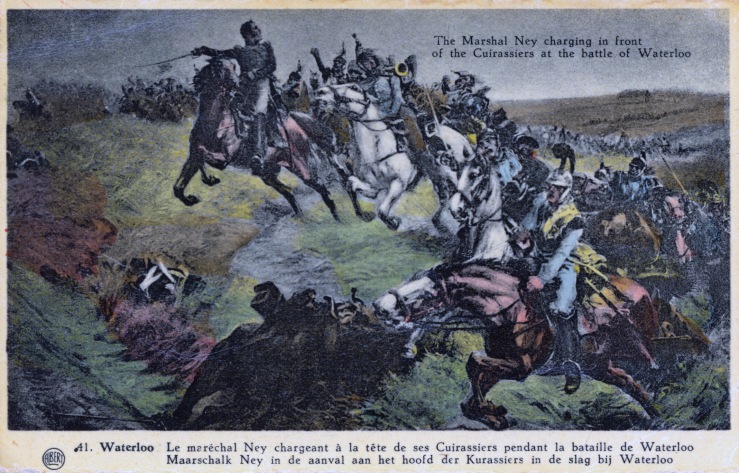

After about 10 miles of cycling, we passed through the village of Waterloo and, a mile or two later, we arrived at the monument commemorating the famous eponymous battle. This was where our very own Duke of Wellington and his Prussian ally Blücher defeated Napoleon Bonaparte, 151 years earlier, in 1815. (Cue Beethoven…)

We had some knowledge of the battle from school history lessons but Martin became a real Waterloo enthusiast as a result of this trip. Over the years to come, he visited the battlefield and its environs many times.

The battle is commemorated by an artificial mound, more than 140 feet high, surmounted by a 31 ton statue of a lion, cast in sections in Liège and assembled in Brussels. In those days, the visitor centre below the mound had the tacky look of a downmarket seaside resort and we did not hang around too long. We were soon on the road, continuing our journey across the gently undulating countryside. Passing through the famous Quatre Bras crossroads, we cycled on to Namur. We reached the town by early afternoon, having cycled a total of 40 or so miles.

Now we were in very different and more dramatic countryside, on the edge of the Ardennes hills. Namur (Namen in Flemish) is at the confluence of the major rivers Sambre and Meuse (the latter known as the Maas in Flanders and the Netherlands). The town was a strategically important location for Belgium and had been besieged within living memory (by the germans in 1914).

In fact, the confluence of the rivers has been defended by a citadel for more than a thousand years. In its present form, the fortress owes much to a 17th-century rebuild by the Dutch. It remained in service until the late 19th century, when it was superseded by a ring of new forts around the town. It’s open to the public and offers great views over the town. It also looks imposing when viewed from the opposite bank of the river Meuse, in the town.

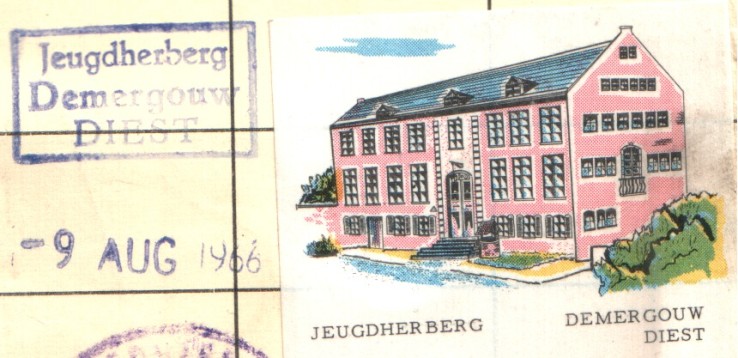

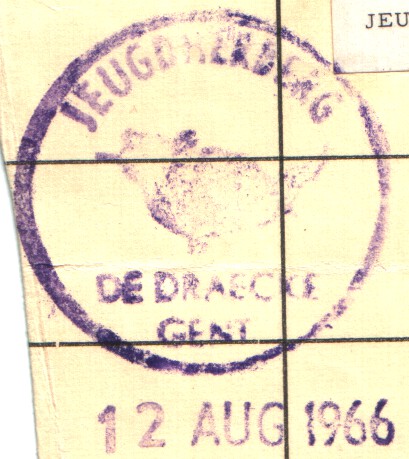

The youth hostel was beside the Meuse, within easy walking distance of the citadel. We booked in and found the atmosphere and regime very similar to the friendly English hostels. (I’d done a hostel-based cycle tour of Berkshire, Hampshire, Sussex and Surrey two years earlier, when I was 15 years old, with another school friend, Paul Maclean.) The main difference was that Belgian hostels would accommodate petrol-powered travellers, whereas English hostels only took hikers and cyclists.

My most vivid memory of Namur is seeing the citadel floodlit at night with the river reflecting the lights of the town below. At an age when I had not yet even had a girlfriend, I thought that it would be a very romantic location to bring a young lady. Decades later, my wife and I spent a night in the town, having driven over from England. It may have taken a long time but I did finally get round to it.

Another less romantic memory is of trying to get to sleep in the hostel dormitory. I guess there were something like eight lads, including ourselves, in the room. We spoke various languages but one thing everybody understood was animal impersonations. Somehow, after lights out, an impromptu animal noise contest broke it. It lasted quite a time and was very puerile. But it was also an absolute hoot, in every sense. Well, you’re only 17 once.

Day 5 – Thursday 4th August 1966

Our next destination was Liège, the capital of Wallonia. In some ways, it was the Belgian equivalent of Manchester crossed with Sheffield: a thoroughly industrialised steel-making city that was also a major cultural hub. Foundries belched smoke just a mile or two from the museums, university and opera house. A city that was home to the religious and those who hated religion; where the Catholic feast of Corpus Christi was first celebrated yet where the original cathedral was destroyed by revolutionaries.

The whole 40-mile journey from Namur was along the south bank of the Meuse. It was a visually attractive and quite rural route. But it was busy, being the main highway between Liège and rest of the Sambre-Meuse industrial region to the west of Namur.

I had never visited an ‘old school’ coal and steel city before: there were no such places in my part of England. Liège was certainly big, very industrial and quite badly polluted: from a distance you could see a orangey-grey sulphurous haze over the city, and the buildings were blackened by a century or more of pollution. Nonetheless, the old parts of the city had a certain gallic dignity. There were some fine buildings, reminiscent of Paris as seen in TV adaptations of Simenon’s Inspector Maigret novels. And that’s quite apt, as Georges Simenon – one of the most prolific and biggest selling authors of the 20th century – was a native of Liège (and, of course, another famous Belgian).

Liège has a very long history and was by no means created by the industrial revolution that it espoused so effectively. The first written reference to the city is in the 6th century. It became the capital of a prince-bishopric, which lasted for 800 years until late 1700s. In rapid succession it became an independent republic, then Austrian, French, Dutch and finally Belgian.

Here’s a little piece of trivia about the name Liège. British people, myself included, often pronounce the name as if it had an acute accent over the ‘e’ – giving a long ‘e’ sound. Until the 19th century, it was indeed spelled Liége, to reflect that pronunciation. But the locals gradually adopted a shorter ‘e’ and so the spelling was officially altered to Liège in official French.

There is also a distinctive (but rapidly dying) French-related Walloon language, in which the city is call Lidje. In Dutch the name is Luik and in German Lüttich: the Netherlands and Germany are but a short drive away. Confused? You certainly can be when travelling in the area. Whenever you cross the now almost unnoticeable open borders, the spelling of the direction signs changes.

In Liège, we couldn’t find a youth hostel affiliated to the International Youth Hostels Association but there was a conveniently central student hostel, the Maison des Jeunes (Young People’s House), which filled the gap very well. I remember ordering a cup of coffee soon after we arrived there. The guy on the bar could only offer Nescafé instant coffee and was very apologetic about this shortcoming. I had to smile, because in our household, Nescafé was regarded as something of a luxury, especially if it was the ‘Blend 37 Continental’ variety (Saturday mornings only).

Before setting out from England, I had asked my Mum if there was anything she would like me to get her as a little gift. She had mentioned a perfume called Molyneux Numéro Cinq. I knew nothing of it and tried in vain to find it in the sophisticated perfume shops of Liège. In fact, I never ever found any anywhere. I learned many years later that it was created in the 1920s and was known as ‘the other No.5’; the famous one being, of course, by Coco Chanel.

My recollection is that, after walking round the city centre, we went to bed fairly early. Tomorrow another country beckoned: we were heading for West Germany. We mustn’t talk about the war, even though our parents never stopped talking about it. And especially, Tom, we mustn’t talk about that football match you attended at Wembley, less than a week ago.

But, joking apart, what could possibly go wrong for us in Germany?

Day 6 – Friday 5th August 1966

The weather on Friday morning was again pleasant. In fact, we hadn’t had a bad day since leaving home the previous Sunday. We cycled off from the student hostel in Liège, through the city centre, towards Aachen. We were excited by the thought of visiting another country, West Germany.

Our target was Aachen, the famous German spa and border town, known historically to the British by its French name, Aix-la-Chapelle. Indeed, I was aware of Robert Browning’s poem ‘How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix’, which was popular with my parents’ generation. We too were travelling from Ghent (which we passed through on Day 2) to Aix but by a rather less direct route.

Aachen was only 27 miles from Liège. We intended staying just one night but, with such a short journey, we planned to spend the afternoon exploring the historic city. It was once the residence of Charlemagne (Charles the Great), king of the Franks. Later, kings of Germany were crowned there. We were particularly keen to visit the famous cathedral.

As Liège stands at the confluence of the rivers Meuse, Ourthe and Vesdre, in the north-east corner of the Ardennes hills, the road to Aachen involves a very long and quite steep climb, away from the rivers, almost as soon as you start the journey. The climb sticks in my mind as the toughest of the entire tour and it felt as if it went on for about five miles at an almost constant steep gradient. In reality, it may have been more like two miles, but it was one hell of a drag and not good for morale first thing after breakfast. However, the view from the top, back towards Liège, did give an impressive view of the city and the smoggy orange-grey industrial haze hanging over it.

Once we had climbed out of the valley, we were in high rolling countryside. Near Battice, I stopped and took this photograph, which shows the view looking towards the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, which lies about 40 miles to the south. The area is known as Hautes Fagnes in French, Hohes Venn in German or the High Fens in English.

This is another area of competing languages, jostling elbow to elbow. We were still just in French-speaking Wallonia but a few miles south was Belgium’s German-speaking area and just a few miles to the north lay the Netherlands. There is said to be a small village in this region where the language spoken depends on the quarter the person lives in. It’s probably a myth but very close to reality.

About 40 years after I took that photo, I was contacted by a Liège-based engineering student for technical advice about Sturmey-Archer gears. By happy coincidence, the bike I rode on that tour had a Sturmey-Archer FW 4-speed gear. I sent him a copy of the photo and, amazingly, he tracked down the location and re-took it. There were some signs of modernisation but it was pleasantly surprising how little had changed.

In that same area, we stopped at a little shop and bought some boiled sweets (or, as Americans would say, ‘hard candy’). We noticed that the colours were much less bright than equivalent British sweets. We guessed this was because the Belgians used less artificial colouring. The sweets looked a lot less interesting than British ones but they tasted fine.

Whilst on the subject of confectionery, as the tour progressed we discovered that Mars bars varied from country to country. I’m talking here not of the American Mars bar (unique to the USA) but the international version, invented in the 1920s by a member of the Mars family in Slough, England (not far from my hometown, Reading) and sold around the world. We found that the balance of chocolate to caramel to nougat varied slightly, depending on whether you bought the Mars bar in Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands or Britain. Sadly, whilst there is a living to be made as a wine expert, there is no financial future for a Mars bar connoisseur.

We also noticed that, like the UK at that time, customers paid a deposit on glass bottles, which was reimbursed when the ‘empty’ was returned to the shop. However, in Belgium there was also a deposit on other glass containers, such as jam jars.

For an hour or more, it was a pleasant ride through the gently undulating Ardennes countryside. Just before the West German border, we were amused to pass through a village called La Calamine. In those days, calamine lotion was found in many a British bathroom cabinet or medical chest. It’s based on a zinc compound and was the universal panacea for sunburn and skin rashes. The village, also known as Kelmis in German, got its name from the mining of the zinc ore used in calamine lotion.

It must have been about noon as we approached the West German border. I recall a mixture of excitement and trepidation. I had read a lot about Germany, a country I found fascinating and admirable in so many ways – the culture, history, landscape, architecture, work ethic and technological ingenuity. But also, there was the shadow of World War 2, which anyone of my generation could not entirely escape. I was born four years after the war ended, but my early years were dominated by the after-effects of the war – rationing, austerity and the older generation’s comments about Germany.

Those comments were by no means all anti-German. There was a recognition that we Brits were a lot like the Germans, with many genetic and cultural links. There was also great admiration of German technology and of West Germany’s post-war economic recovery. It was often said (and sometimes still is) that Britain won the war but lost the peace: the conflict ruined Britain financially and it took us 60 years to pay back the USA for the money we borrowed to fight the war. So we Brits had this mental baggage regarding the Germans: a mixture of admiration and respect coupled with incomprehension as to how Hitler had been allowed to go so far. As a naive 17-year-old, I found it all rather puzzling but very interesting.

It was important, to bear in mind that, following post-war partition, there were two Germanys: the Federal Republic of Germany (which we called West Germany) and, behind the ‘Iron Curtain’, the communist German Democratic Republic (East Germany). And, entirely surrounded by East Germany, was Berlin, the former German capital, itself divided into Western and Eastern zones by the infamous Berlin Wall, erected five years earlier.

Entering the Federal Republic of Germany, we would also have to come to terms with another currency. Farewell (temporarily) to the Belgian franc, at 140 to the British pound, with each of its centimes worth a mere 0.017 of an old penny. Now we needed the Deutschmark, the West German mark. There were just over 11 marks to the pound and each mark comprised 100 pfennigs. So a mark was worth approximately 1 shilling and 10 old pence (£0.09) and a pfennig was worth about 0.22 of an old penny. (Trivia gem: In Tudor times, England had its own mark, which was worth two-thirds of a pound. Not a lot of people know that!)

As we approached the border between Belgium and West Germany, it was very clear that we were entering another country. I have a recollection of tall, dark trees (cue Grimms’ Fairy Tales) and telecommunications or reconnaissance masts on the German side of the border. Just a hint of Mordor. Anyway, we were allowed in without any problems and were soon cycling downhill on a very smart and modern concrete cycle path, bordered by grass. We were now in North Rhine-Westphalia, the Federal Republic of Germany’s most populous state. All seemed to be going well, very well, perhaps too well…

With typically teutonic attention to detail, the top of the cut grass was level with the concrete surface. This looked very neat but spelled disaster. In a moment of inattention, Tom let his front wheel go off the concrete and onto the grass. Instinctively, he steered back onto the concrete. This would have been a good idea but for the fact that, for the top of the grass to be level with the concrete, the earth had to be several inches lower. So the lightweight alloy wheel rim crashed into the sharp edge of the concrete and bent Tom’s wheel. Tom was unhurt but the wheel now would not turn, so the bike was unrideable.

There was only one course of action open to us: walk a couple of miles into Aachen, dragging the damaged bike, and find a cycle mechanic to fix the wheel. This we did and the bike shop we found did a good job, quickly and at a reasonable price. The owner and his assistant were also very interested in my Moulton; they came out of the shop and spent some time examining it and discussing it. Meanwhile, I was amazed to see in their shop window that some new German roadsters still had plunger brakes, with a brake block pushing down onto the front tyre. Such crude brakes had not been used on British bikes for maybe 60 years.

With Tom’s bike fixed, we went in search of something to eat. We found a wonderful-looking cake shop and I bought a piece of chocolate cake. It looked really tasty and had been steeped in rum or brandy. To my surprise, I found it quite disgusting and completely inedible. In fact, for some time after, the very thought of my first bite of German cake made me feel queasy.

Now, to add to our woes, the weather broke. After a lovely sunny morning, we endured a thunderstorm – the proverbial donner und blitzung – and for the rest of the day showers came and went. We had lost a lot of time, so we decided it would be best to get our accommodation sorted out before doing anything else. The plan was to stay a night in the Aachen youth hostel.

It was my father who got me interested in youth hostelling. He had done it as a young man in the inter-war years. He told me about how youth hostelling was a great German idea. He even had a booklet about the German origins of youth hostelling. We therefore had a belief and expectation that German youth hostels would be like the English ones but so much better. Now we would find out.

It was about 2.30 in the afternoon when we arrived at the Aachen hostel. It was massive, very modern and rather impersonal; more reminiscent architecturally of a 1960s British secondary school than the small, cosy and domestic-scale English hostels with which I was familiar. A big surprise was seeing a huge modern motor coach in the car park, which had arrived full of well-dressed German schoolchildren and their well-dressed teachers.

We made our way to the reception area and approached the enquiries position. There was a member of staff working in the office. We indicated to him that we wanted to book in. He scowled and indicated that the office did not open until 4.00. So we had to wait for an hour and a half.

This we did, in the company of a small number of people in the same position as ourselves: people from around the world who looked like ‘real’ hostellers. Meanwhile, well-dressed teachers and schoolchildren swanned in and out. This was plainly an environment tuned to their needs, not to traditional hostellers.

With typical German efficiency, on the dot of 4.00pm, the official open the enquiry window. Hurray, we thought, now we could book our stay. But, what’s this? He tells everyone that the hostel is fully booked up. Plainly, he knew this when we arrived 90 minutes earlier. Welcome to German bureaucracy, inflexibility and schadenfreude – defined as ‘pleasure derived by someone from another person’s misfortune’.

So, the afternoon was almost over. The combination of the crash and being messed about by the hostel management meant we were not going to see the sites of Aachen. But we still needed somewhere to sleep.

The suburbs of Aachen spread right up to the Dutch border and we knew there was another hostel, just over the border in Vaals. We decided to give it a try and cycled off in that direction. After two or three miles, we crossed the Dutch border, notching up our third country of the day, and soon reached the hostel. There we were greeted by a very friendly and accessible warden, but sadly, his hostel was also full. ‘I wish I had a hundred beds,’ he said. This was turning out to be quite a bad day. Was this somehow Germany’s revenge for the decisions of the referee in last Saturday’s soccer World Cup Final?

What to do? As a long-stop, we had brought a three-man tent with us, but we had no sleeping bags other than the thin sheet ones required by youth hostels to save them from laundering sheets. We decided we would have to find a barn to sleep in or somewhere to pitch a tent. It was now about 5.00pm, it was raining much of the time, and the sky was heavily overcast.

Martin had a small methylated spirits stove but no fuel. It seemed a good idea to get some and eventually we managed to buy some brennspiritus, which we discovered was the German name for meths.

We crossed back into West Germany and headed in the general direction of Cologne (Köln), our next planned stop. It was so wet at times that we had to wear our waterproof capes and sou’westers, which made cycling that much drier but also more awkward. As we rode across the flat but wind-swept Cologne Lowland (as this area is known), we were surrounded by huge fields of cereal crops in the foreground and mining machinery on the horizon. We kept an eye open for farmhouses but didn’t get any response from the first one we tried. Maybe the occupants were cowering behind their curtains in fear of this strange trio of tired, hungry, thirst and anxious foreign teenagers.

Eventually, about 7.30 in the evening, near the village of Gürzenich, a few miles from the town of Düren, we struck lucky. We found a farm inhabited by some of the friendliest people you could hope to meet. I think the house was divided into two parts, as the people seemed to comprise two families, possibly related. These friendly folk took us in and allowed us to take over a corner of their barn. They sold us some fresh eggs which we must have boiled for supper, using Martin’s meths stove.

The idea of spending a night in a barn may sound very attractive, if you have in mind a warm, enclosed building with lots of soft, clean hay to nestle into. Something straight out of an Enid Blyton novel. However, this barn, on the windy lowland, was open-sided and contained only machine-compressed straw, which was about as soft as chipboard. There was no way you could nestle into that. With no sleeping bags, and only a small tent to lay over the three of us as a makeshift blanket, this was going to be a challenging night.

Day 7 – Saturday 6th August 1966

In the early hours of Saturday, I found myself awake and almost delirious. I was desperately thirsty. But in the draughty barn, on the dark Cologne Lowland, we had nothing to drink.

The previous day had been very arduous. Instead of an easy 27 mile ride followed by an interesting afternoon sightseeing and a night in a world-class youth hostel, we had faced one challenge after another. The longest, hardest climb of the tour; Tom’s crash, the walk into Aachen and getting the bike fixed; the thunder and rain; being messed about by the Aachen youth hostel management; the excursion into the Netherlands in the unsuccessful quest for accommodation; and the stressful, gloomy and wet ride east, in search of somewhere to stay for the night. Amongst all that hassle, we had not eaten well, and I had drunk far too little. I was now badly dehydrated.

I was also probably feeling the effects of Gilbert’s Syndrome, a genetic condition I did not know I had until 32 years later. A lot of people (mostly males) have Gilbert’s Syndrome. It tends to manifest itself in the teenage years. There’s no money to be made out of studying it or creating pharmaceuticals to treat it, so the medical and scientific world largely ignores it. Many doctors and nurses have little or no knowledge of it and the medical profession tends to play it down as having no harmful effects. The only upside is that having Gilbert’s Syndrome is believed to reduce slightly the risk of heart attack.

However, for some people Gilbert’s Syndrome can be quite a problem. Quite apart from the fact that it can lead to a false hepatitis diagnosis, it can easily result in a case of ‘instant jaundice’ if you over exert yourself and/or miss a meal and don’t drink enough non-alcoholic fluids. (Alcohol just makes the effects of Gilbert’s Syndrome worse.) There is also a nasty servo effect: miss a meal and you lose your appetite, just at the time you most need to eat. It’s very easy then to start spinning into a spiral of gloom.

However, once you know you’ve got it, and that you can modify your lifestyle to cope with it, life becomes easier. But I was in my 50s before I knew I had it and even then, finding out reliable information about its effects was not easy. Up to that point, I just thought I was a bit of a wimp. Now I can manage it and I understand my limits much better. I know not to defer or miss meals and I know how quickly I can recover from a mild attack, especially given a nice cheese and ham roll!

I knew none of this as a 17-year-old in 1966. So, at maybe 1.30 in the morning, I was so desperate for water, that I got up and stood outside the farmhouse. I cried out what I thought was the German word for water. Nothing happened, so I chucked a little pebble or two at the bedroom windows. Eventually just about everybody came out of the house. I then discovered that, in my delirium, I’d been saying the Dutch word for water (spelled water but pronounced vahter) which to our German hosts sounded as if I was calling for my father (vater is German for father, whereas water is wasser). Considering that I’d disturbed the sleep of about eight people, they were very kind and understanding. Most importantly, they provided me with plenty of water. After that, I managed to sleep a bit.

In the morning, Tom, Martin and I got up and, after breakfast, thanked our very kind and tolerant hosts before getting back on the road. The previous day, we’d travelled 24 miles more than planned but the upside was that we were only 27 miles from Cologne. (Which in those days we Brits always spelled the French way, whereas today we increasingly use the German spelling, Köln.)

But despite the relatively short distance ahead of us, we were still suffering the after effects of ‘Black Friday’ and I continued to feel quite poorly. Mercifully, the weather was good that Saturday morning and the terrain continued as before, mostly flat, as we headed east over the Cologne Lowland. Then, dropping down towards the Rhine valley, we reached the western outskirts of Cologne about midday. This is where a minor miracle took place.

I was still feeling the effects of dehydration. Sometimes, your body seems to know what you need to eat or drink when you are feeling ill. It’s like the way cats know that they’ll feel better if they eat a bit of grass. Plainly, at an intellectual level the cat hasn’t a clue, but something tells it what to do. It was like that with me and a sudden craving for Coca Cola. And, lo and behold, a nearby shop in this German suburb had litre bottles of the stuff. Yes, litre bottles!

A litre bottle of anything was almost miraculous to a Brit in those days. (Think the ape-men in the film 2001, transfixed by the big, black obelisk.) Nothing in the UK came in such a large bottle: we were used to half-pints, pints, splits, half-bottles and wine bottles, but nothing bigger than about two-thirds of a litre. Bearing in mind the gigantic bottles of soft drinks that you can buy everywhere today, it’s had to understand how amazing a litre bottle seemed. But believe me, for us it was truly awesome!

So, I bought a litre bottle of Coke, sat on the pavement (sidewalk) and drank it. It must have looked a bit odd to the Germans but I was oblivious to that. Almost immediately, I felt very much better. Years later, I discovered that cola (particular when flat) is widely believed to aid rehydration, in the absence of proper oral rehydration drinks. The diuretic effect of the caffeine must have been counterproductive but the caffeine kick certainly perked me up. Anyway, whatever the scientists say, it did the trick for me: a little curb-side miracle in suburban Cologne.

After that, we proceeded into the centre of Cologne and booked into the youth hostel. This time there were no problems registering. The hostel was, like the Aachen one, big, modern and impersonal, but it served its purpose. There were a lot of rules and woe betide anyone who transgressed them. There was a curfew at 8.00pm and silence was imposed from 10.00pm. It was evident that obeying orders was a very important part of German life.

My impressions of Cologne itself were of a thriving and very large city, combining efficient modernity with a long and rich cultural heritage. The Gothic cathedral, which houses what are supposedly the relics of the three wise men, was particularly impressive. I had seen an aerial photograph of Cologne after it had been bombed during WW2. The Royal Air Force dropped nearly 35,000 tons of bombs on the city. The devastation of the city centre was almost total and truly looked similar to Hiroshima after the atom bomb. It’s amazing that the cathedral survived, especially as it was hit by 14 British bombs. It was most impressive to see the rebuilt city, the biggest in North Rhine-Westphalia, just 21 years after the end of the war.

In my home town, they’ve been arguing for a century about building a new bridge over the Thames and still nothing’s happened. But, whilst the Luftwaffe did shoot up Reading town centre on one occasion, it was but a fleabite compared to what the RAF did to Cologne. Germany paid a high price to have its urban landscape remodelled.

Cologne was a name very well known to Brits in the 1960s. For a start, the perfume eau de Cologne was very popular, both with men and women. If you didn’t know what to give someone for a birthday or Christmas present, eau de Cologne was high on the list of possibles, along with the inevitable book token. Best known and widely advertised in Britain was the brand 4711, named after the address in the city’s Glockenstrasse where production started in the late 18th century. But Cologne was also known because of the British Army on the Rhine (BAOR), the army of occupation in the Rhineland and the northern part of West Germany from 1945 until 1994. Many British families had members who, at some time or another, were stationed with BAOR. In those days, no Dover-Ostend ferry crossing was complete without a bar full of British squaddies, en route to or from BAOR, imbibing substantial quantities of beer.

Because of the BAOR, there was a very popular radio programme called Two-Way Family Favourites. This show came on the air at noon on Sundays. It was on the BBC Light Programme, which in those days was on 1500 metres long wave (200 kHz) and could be received over the whole of the UK and most of north-west Europe. In West Germany, the programme was also on the British Forces Broadcasting Service (BFBS), which had studios in Cologne. There were two presenters, one at the BBC in London and one at BFBS in Cologne, and they played requests and dedications to and from British forces and their families and friends.

The programme was so popular that, on a hot summer’s day in suburbia, you could walk down a street and hear the show booming out of almost every open window. There must be many older Brits like me who still have a Pavlovian reaction to the show’s theme tune, With a song in my heart: we instantly start drooling at the thought of Mum’s roast beef and Yorkshire pudding, the standard British Sunday lunch of that era. Back then, if you were listening to Family Favourites, chances are you were either eating Sunday lunch or smelling it being cooked. Ah! Bisto, to coin a phrase.

We three lads were pleased to have reached Cologne. This was as far away from home as we were venturing, as we only had a fortnight and limited funds. A lot had happened in just one week since Tom witnessed the England football team beat West Germany at Wembley. We had now reached the mighty Rhine, so much bigger than the Thames. Tomorrow we would cross it and start the second half of our tour.

Day 8 – Sunday 7th August 1966

After a much-needed good night’s sleep at the Cologne youth hostel, we breakfasted and performed the housekeeping tasks allocated to us by the hostel management. We were then free to leave and we headed off for our next destination. This was Düsseldorf, about 24 miles of flat and easy cycling away. The weather was mild, though the sky was overcast. We crossed the Rhine to its eastern side via the Mülheim suspension bridge and then followed the road north-north-west through the town of Leverkusen.

The Agfa-Gevaert transparency film in my borrowed camera had the cost of processing and mounting included in the purchase price, as was often the case in those days. It was ironic that the address to which the film had to be sent for processing was in Leverkusen, the very place we were cycling through. The film was presumably made in Leverkusen then exported to England, before being briefly brought back to Leverkusen by me before being taken back to England, then posted back to Leverkusen, and finally returned to me in England. Those pictures had clocked up a lot of miles by the time I finally saw them.

Travelling in West Germany, we noticed several things that were new to us. For example, there were lorries with tail-lifts, something we had never seen in the UK. Also, some of the trucks had lift axles, so that the number of wheels on the road could be varied: we’d never seen that, either. It was a long time before tail-lifts and lift axles became common in Britain. To use, it was just another sign of how advanced and modern West Germany was.

In all our travelling, we constantly encountered types of automobile that were rare or unknown at home. In those days, foreign cars were rare in Britain, and boys like me were very interested in the German, French and Italian vehicles we encountered. Even the colours were different, with many more light-coloured cars on the European mainland. A white car was a rarity in Britain: a cynic might say (with some justification) that this was to mask the inevitable body rust.

As we entered each town or village, we noticed a standard format sign indicating the dominant religion of that community and the days and times of church services. Like Belgium, the Rhineland was strongly Catholic, so most places advertised Heilige Messe (Holy Mass). But there were also signs for the Lutheran Evangelischer Gottesdienst (Evangelical service). I think these signs are still used, with a yellow church symbol for Catholics and a purple one for Evangelicals.

We made good progress to Düsseldorf, the capital of North Rhine-Westphalia, which by happy coincidence was twinned with our home town, Reading. The main part of the city is on the east bank of the Rhine but the hostel was just across the river on the west bank. We crossed via the Rheinkniebrücke, which means literally the Rhine knee bridge, the knee being a sharp bend in the river.

After lunch at the hostel, we joined a happy horde of hostellers on washing up duty in the large kitchen. Holding court was an amusing German chap, doing impersonations of various English language radio stations and their station identifications. His repertoire included the BBC Light Programme and the American Forces Network, both of which had large audiences in West Germany. I’m pretty sure that what set him off was a kitchen radio playing the BBC’s aforementioned Two-Way Family Favourites.

Like the Aachen and Cologne hostels, Düsseldorf’s was a large, modern and typically 1960s building, with lots of glass. Sadly, there was a bit two much glass, and poor Martin walked straight into an almost invisible glass door, nose first. It was a hell of a whack, giving him a bad nose bleed and he suffered the after effects for some considerable time afterwards. Having witnessed Martin’s accident, I can understand why some countries, such as England, now require conspicuity markings on glass where its presence might not be obvious.

In the 1960s, Düsseldorf had an international reputation for being an upmarket bright and thoroughly modern place: a centre of finance, business and fashion. We wandered around the city and soaked up the atmosphere, which to us provincial suburban teenagers seemed very sophisticated and beguiling. Reading may have been twinned with Düsseldorf but in those days it wasn’t quite in the same league!

We were by now getting to know the local cheap foods and beverages. Apart from the ubiquitous American cola brands, there was something new to us: Fanta orange drink, something you never saw in England. (Only years later did I discover that it was a World War 2 German creation, devised when American cola ingredients were embargoed.) And, of course, it didn’t take long to work out that hot German sausages, such bockwurst or bratwurst, were widely available, tasty and filling.